This is Scientific American's 60-second Science, I'm Christopher Intagliata.

Our solar system is far from the only way to put together stars and their planets.

"If you look at all the stars, you know, in our galaxy, in the Milky Way, right? More than half of the stars are formed in multiples—meaning there's more than one star in the system."

Astrophysicist Jaehan Bae of the Carnegie Institution for Science. He has studied one of those systems—with three stars. It's called GW Orionis. And it's freshly formed—only a million years old.

"Yeah, it's really, really young. Yeah, it's a baby."

Bae says if you translate that million-year life span to that of a human, it's the equivalent of a week-old baby. And how many week-old babies do you bump into?

"So if you just walk around your neighborhood, there's little chance you meet a baby who's one week old, right? So, first of all, it's hard to find these systems—they're pretty rare."

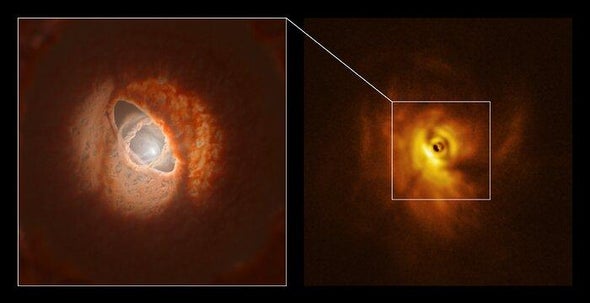

Bae and his colleagues got lucky spotting this one. Using radio telescopes, they were able to image the star system. And they say it differs from our own solar system in more than just star count.

In our solar system, for example, all eight planets orbit the sun more or less in a single plane. Think of the sun as the center of a vinyl record—with the planets strung out along the grooves.

In contrast, Bae's team discovered that the stars in this triple-star system are ringed by clouds of dust in multiple warped and misaligned planes—picture a three-dimensional gyroscope rather than a two-dimensional vinyl record. The observations are in the journal Science.

Those rings of dust will presumably go on to form planets as the star system matures. And Bae says astronomers have indeed observed other, more mature star systems—with planets orbiting in these misaligned planes.

"And we wanted to understand if that happens when the planets are born or whether it's some evolutionary thing that happens over, you know, a billion years."

The finding suggests that weirdly aligned planetary systems are born that way—and that stars and their embryonic planets can be all topsy-turvy—even in their infancy.

Thanks for listening for Scientific American's 60-second Science. I'm Christopher Intagliata.