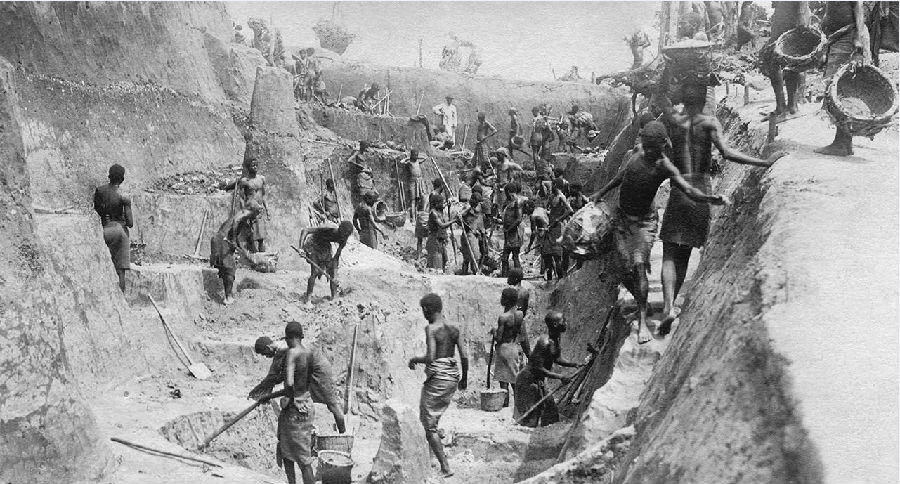

The railway was the idea of Pietro Paolo Savorgnan di Brazza, an Italian-born French explorer who conquered much of central Africa for France “by exclusively peaceful means”. The French state imagined itself as a bringer of civilisation to Africa, and the railway was to provide a way for the Congolese to take part in world trade. Yet Mr Daughton shows how the colonial administration in Congo had little capacity to build a railway without violence: it claimed to be recruiting paid volunteers while its agents forced Africans to work at gunpoint. Many were marched hundreds of kilometres to the tracks chained at the neck, as slaves had been a century before. Whatever work had to be done, reported Albert Londres, a French journalist, “it’s captives who do it.”

这条铁路是意大利出生的法国探险家皮埃特罗·保罗·萨沃格南·迪·布拉扎的主意,他“完全通过和平手段”为法国征服了中非大部分地区。法国政府把自己想象成把文明带到非洲的人,而修建这条铁路是为了给刚果人提供一条参与世界贸易的途径。然而,道顿指出,刚果殖民政府在不使用暴力的情况下几乎没有能力修建一条铁路:它声称招募有偿志愿者,而其代理人则用枪逼着非洲人工作。许多人像一个世纪前的奴隶一样,脖子上被铁链锁住,被押送到几百公里外的铁轨上。法国记者阿尔伯特·朗德雷斯报道称,无论要做什么工作,“都由俘虏来做。”

The evil caused by perverse incentives recurs throughout the book. The Societe de Construction des Batignolles, a contractor, was assigned the job of producing the railway and paid a fixed fee. But whereas it had to provide machinery and skilled labour itself, the unskilled labour of Africans was given to it by the colonial state, practically free. It was cheaper to replace workers who died with new ones than to keep them healthy. In 1925 one doctor estimated nearly a quarter of new workers would not survive a year.

由不正当动机引起的邪恶在整本书中反复出现。承包商巴蒂尼奥勒建设公司被指派负责这条铁路的修建工作,并收到了固定的款项。但是,尽管它必须自己提供机器和熟练劳动力,但非洲的非熟练劳动力却是由殖民国家提供的,几乎是免费的。用新的工人取代死去的工人比保持工人们的健康更便宜。1925年,一位医生估算,近四分之一的新工人活不过一年。

Surprisingly, the French state documented these abuses diligently (the archives provide the source of much of Mr Daughton’s information). In 1926 one inspector, Jean-Noel-Paul Pegourier, compared the treatment of workers on the railway to the German genocide of the Herero in Namibia before the first world war. Yet unlike the reports of Leopold’s abuses, these observations had little effect, not least because orders issued from Paris or even Brazzaville were simply ignored. Raphael Antonetti, the colonial governor, fought back with an avalanche of legalese.

令人惊讶的是,法国政府勤奋地记录了这些虐待行为(档案提供了道顿先生的大部分信息来源)。1926年,一名检查员让-诺埃尔-保罗·佩古里尔将铁路工人受到的待遇比作一战前德国在纳米比亚对赫雷罗人的种族灭绝。然而,与利奥波德虐待的结果不同的是,这些观察结果收效甚微,尤其是因为来自巴黎甚至布拉柴维尔的命令完全被忽视了。殖民地总督拉斐尔·安东内蒂用连珠炮似的法律术语予以反击。

The railway was a masterpiece of engineering, as Mr Daughton readily admits. For decades it provided the only means of transporting goods within Congo. The wealth of Brazzaville, still so named, was built on it. In Britain and France, the infrastructure bequeathed to former colonies is often cited as an argument for its benefits. But to build it, a weak and stingy state had to rely on brutality. As Mr Daughton reports, “the Congo-Ocean provides an all-too-useful case in point for how the language of humanity could be invoked to explain the deaths of thousands.”

正如道顿先生欣然承认的那样,这条铁路是一项工程杰作。几十年来,它是刚果境内唯一的货物运输途径。布拉柴维尔(至今仍使用这个名字)的财富就建立在它的基础上。在英国和法国,遗留给前殖民地的基础设施经常被拿来作为证明其有利之处的理由。但是为了建立它,一个软弱而吝啬的国家不得不依靠残暴。正如道顿所说的,“刚果-海洋铁路提供了一个非常有用的例子,展示了人类语言是如何被利用来为数千人的死亡辩解。”

译文由可可原创,仅供学习交流使用,未经许可请勿转载。